Mechanised Morality - Part 2 - Normative Ethics

Can normative ethics be applied to an AI?

Introduction

This is a continuation of a previous article that can be found here.

We’ll go deeper into normative ethics and how these apply in the context of our AI insider building on the concepts from the prior article.

AI systems are generally purported to be designed as safe and to not produce harmful or unlawful content . . . whatever the hell that means. Developers of AI models typically will have a statement on their corporate website about the ethics applied to their pre-trained models. This might be in the form of published principles, standards, or similar. The problem largely is they tend to discuss the outcome of a given action, something which cannot be predicted. They will state that they will remove bias or ensure that outcomes are fair and equitable. Whilst this all sounds nice it’s a functionally broken approach, but we’ll come back to this.

But what happens when an AI does not share the same values as the organisation in which it is operating? We might see that decisions or actions over time will deviate from those made by a human operator performing the equivalent duties. We might see that decisions and actions are taken with a different consideration for ‘risk’. This could be giving product guidance to customers or making decisions about who can access those products. An AI in this role might be building a book of business that will become problematic over time. These scenarios, perhaps, might be the passive AI insider that is just operating in a slightly different way. It is the scale problem and the differentiator is likely to be in the fringe cases or the extremes. An AI does not have individualisation within a population like a workforce would do where differing opinions provide corrective mechanisms. This could be an easy fix, multiple instances with different personas for example, but this is exasperated by the scale problem.

Ethics in AI

We might imagine how morality or values can be codified within a system. Normative ethics falls into three families of moral theories.

Consequentialism

This requires making determinations about the consequences of an action. What is morally right depends on the outcome of that action.

Deontological

This requires a defined set of obligations, permissions, and prohibitions to determine if an action is morally right.

Virtue ethics

This deals with character traits, habits, practical wisdom, and dispositions.

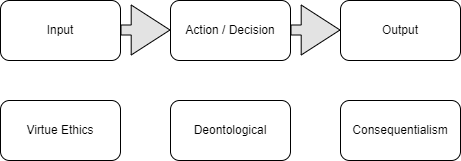

A digestible way to conceptualise this against a decision-making process would be something along these lines.

Virtue ethics deals with the conditions and context of the rational actor making the decision. The deontological talks to the action or decision itself being right or wrong. Consequentialism deals with the consequences of the action after it is made.

Virtue Ethics

There are significant problems with virtue ethics and any application within an AI system in that it is subjective, highly contextual, and very human in nature. We can’t, for example, impart practical wisdom to an AI. An AI lacks the biological mechanisms to experience emotion in a way that humans do and that makes a practical application unviable. Shannon Vallor makes an argument for a Global Technomoral Virtue Ethic in the book Technology and the Virtues, however this doesn’t seem to talk about the ethics of an AI rather the ethics of the practitioners as part of a Global Community.

Whilst Vallor argues a considered position on how we might be able to determine what is good, these will never be ubiquitous concepts. At the point we have introduced governments and corporations into the conversation then the grounds for agreement will be the vacuous and represent only lowest form of performative drivel. We see this now in the stated principles of AI from most big tech companies.

That being said, there are some aspects of virtue ethics we can assess. We can look for traits and habits through testing the AI which might be determined through sampling or monitoring methods. Dispositions can be assessed against an AI persona. These are surface level and don’t really explore virtue ethics in depth, but this might be a good way to understand any unstable elements before we allow the AI access to anything of importance.

Deontological

The least ambiguous application of normative ethics are those which are rule based. We are talking about deontological norms which consist of obligations, permissions, and prohibitions. As you can imagine, these are the easiest to codify within a system and we see some examples of this currently.

Anthropic Claude uses a constitutional model whereby the model evaluates its own responses against the constitution that is defined. This can address the scale problem to some degree but validation it is operating correct would be well advised. Anthropic seem to find agreement with Vallor’s idea of a Global Community and suggest that a wider societal process for the development of such constitutions or deontological norms to govern AI will emerge. Anthropic build their constitution from a number of sources including the UN Declaration of Human Rights, research sets, and Apple’s terms of service (oddly).

LlamaGuard 3 gives us another way example of deontological norms applied. It is similar to constitutional model employed by Anthropic in that checks are applied based on specified criteria. The criteria is where it differs from Anthropic electing to orient itself around the MLCommons standardized hazards taxonomy. It details a number of prohibitions as you would expect. In both cases the rules which govern the decisions and actions from the AI are configurable and customisable to the needs of the organisation.

We can make assessments of deontological norms within a constitution or hazard taxonomy and make a determination about the suitability of those norms relative to an organisational context. The subscribing organisations need to be in agreement with that constitution or the set of rules in which responses are filtered. In an unexpected flash of insight from NIST they include controls within their AI Risk Management Framework relating to alignment of AI to organisational values (GV-5.1-004, GV-6.2-014 & GV-6.2-015 if you are inclined to check). This tends to run counter to views like those of Vallor or Anthropic who advocate for a global (or wider societal) set of AI standards or constitutions. There will always be areas of disagreement when discussing values because they are not formed in isolation and are rooted in political philosophy.

When we apply this back to the scenario of our AI insider we should consider if these deontological norms were checked for alignment with organisational principles. We need to continue checking that these mechanisms work effectively and aren’t silently transforming into something else.

There are problems with the current formulations of deontological norms as applied to AI in that they are unclear and overly subjective. For example, a number of Anthropic’s statement are formulated with statements such as “least likely to be viewed as harmful or offensive”. Whilst I appreciate the sentiment, things like offence aren’t something that can only be determined by the person receiving the response and personally, I wouldn’t want anyone, or anything else else to be making value judgements about what I might be offended by. We can’t mediate the fragile feelings of others and should not seek to do so. The late, great, Hitch know how to deal with such people.

If someone tells me that I've hurt their feelings, I say, 'I'm still waiting to hear what your point is’.

Christopher Hitchens

But this is a problem of rules based criteria. The current applications of it veer into consequentialism through its lack of definition.

Consequentialism

Clearly, we have a problem with consequentialism in the context of an AI within an organisation. It requires that there is a desired state to be achieved which needs to be codified within the AI. The AI principles of most big tech companies fall prey to fashionable word salads. They have a desired state they believe how it ought to be. This is reflected through these principles. How an outcome is achieved is not a consequence of a rules or principle, it is a target state of utilitarian design. The AI can have no knowledge of the outcome, so it has no mechanism to understand if any action can be considered moral. If we consider this in the context of our AI insider, it might just be that the actions it takes are not related to any moral framework based on rules or principles, but it might be acting towards the target state desired by its developers. But the reality is that it will play out in unexpected ways.

One company advocates within their standards for the identification and prioritisation of demographic groups to ensure fairness in outcomes. Consider that for a moment, if we applied this to mortgage acceptance rates and applied fairness criteria on demographic metrics i.e., we would not expect to see disparities between groups. Would we be providing mortgages to those who couldn’t afford to repay it? Well, we know they answer to that question and that was the subprime mortgage lending which was the catalyst for the 2008 economic crisis.

In some sense consequentialism fails because we cannot know the future and the outcome of a given action or set of actions. We are subordinating the individual rights to a perceived greatest possible outcome. Concepts like equity are explicitly political. These are indicators we can practically apply and check. We can look to the stated values of the developer and make a assess if they are applying consequentialist ethics. The environment in which an AI is created can give us insight into the imparted value system. In the context of our AI insider, we must understand that other organisations might have a social agenda that conflicts with the values of organisations we operate in. This is especially true if the AI has originated from other territories where accepted political and value norms differ.

It’s all politics

Inevitably politics has to come into the conversation. It’s the conversation no one wants to have unless there is some public shaming to be done. It’s not a controversial statement to make that AI will have embedded values, and those values will likely reflect those of the developers. Their creation will be of their own image to a large extent.

The problem with most organisations is that they are too lazy or too afraid to openly discuss what their values are. Not properly or honestly, not at a level that is useful. They resort to ill-defined vagaries that don’t survive first contact with gently scrutiny. Obviously this becomes a problem if you are trying to assess alignment of a 3rd party created AI to the organisation. How many companies have started including phrases like ‘authentic’ to describe their values? Borrowed terms from inauthentic online influencers do not make values but this is becoming more and more common.

Hartmann et al published a paper regarding the political ideology of conversational AI. They give the example of ChatGPT being left leaning and articulating a number of positions that are politically biased. It punctuates the point that the training and evaluation stages in the AI lifecycle (as described in the first article) are factors in generating an embedded value structure within the AI. The developer of the AI themselves acknowledge this too.

We are forced to consider the possibility that the political values installed within our AI insider are at odds with the organisational objectives. If you were in an oil company, would you deploy an AI that takes positions against fossil fuels and has a green bias to it’s ideological precepts? I suspect not.

Conclusion

We see that a deontological framing of ethics is the best option at this point given the practical implementation problems with virtue ethics and consequentialism. This is what we see happening with developers of those tools. There is a problem with a lack of definition of deontological prohibitions in that they are overly vague and subjective.

Political considerations come into the mix and this will make people uncomfortable engaging in the conversation but denying its existence doesn’t mean it’s not there.

The next article with deal with deontological norms in the context of Robocop.