Mechanised Morality - Part 3 - Robocop vs. The Compliance Trap

How Classical Liberal Philosophy Dooms AI Ethics to a Technological Dead End

Introduction

There’s some chatter in security circles about ethics, especially as AI begins to emulate human decision-making within organisations. This is only natural. These technologies increasingly mirror human behaviours, particularly in contexts where decisions and outcomes are involved. We must evaluate and calibrate the behaviours of these systems against their human counterparts.

I’ve already covered why organisations applying ethics to AI technology is catastrophically flawed in the previous article in this mini series.

Now I want to address a specific contradiction introduced by how governance is approached, specifically compliance. Compliance can be defined as a state of adherence to a set of rules. It is binary: you either comply or you don’t. This framing is bereft of nuance, void of context, and subject to abuse. It offers a false assurance of protection. I’d go as far as to say that contemporary compliance is little more than overpriced snake oil.

It would be useful to give a definition of terms. Moral and ethic are used interchangeably but they have a specific context. Morality deals with an internal perception of right and wrong, a conscience if you will which pertains to an individual. In the framing of normative ethics then this would be the realm of virtue ethics which is about character. Ethics are broader and are statements of permissions and prohibitions derived through consensus, they pertain to a group. It is possible for an ethical act to be amoral. Ever heard of a politician using legal loopholes for tax avoidance purposes? Whilst this might be ethical and technically correct, it is generally considered amoral by the broader population when the veil is lifted.

Human behavioural defect

Ethics don’t need to be moral. Very often, people within organisations perform actions that are amoral, wrong, and improper but justified through tenuous rationale. This stems from the perception that anything is permissible if it isn’t explicitly prohibited by a policy or standard.

The consequences of this behaviour can be severe: wholesale abuse of personal data, exposure of systems to undesirable conditions, and inadequate levels of protection. These implications are wide-reaching and speak to a fundamental problem. Namely, that too many people will undertake actions that are compliant, not moral.

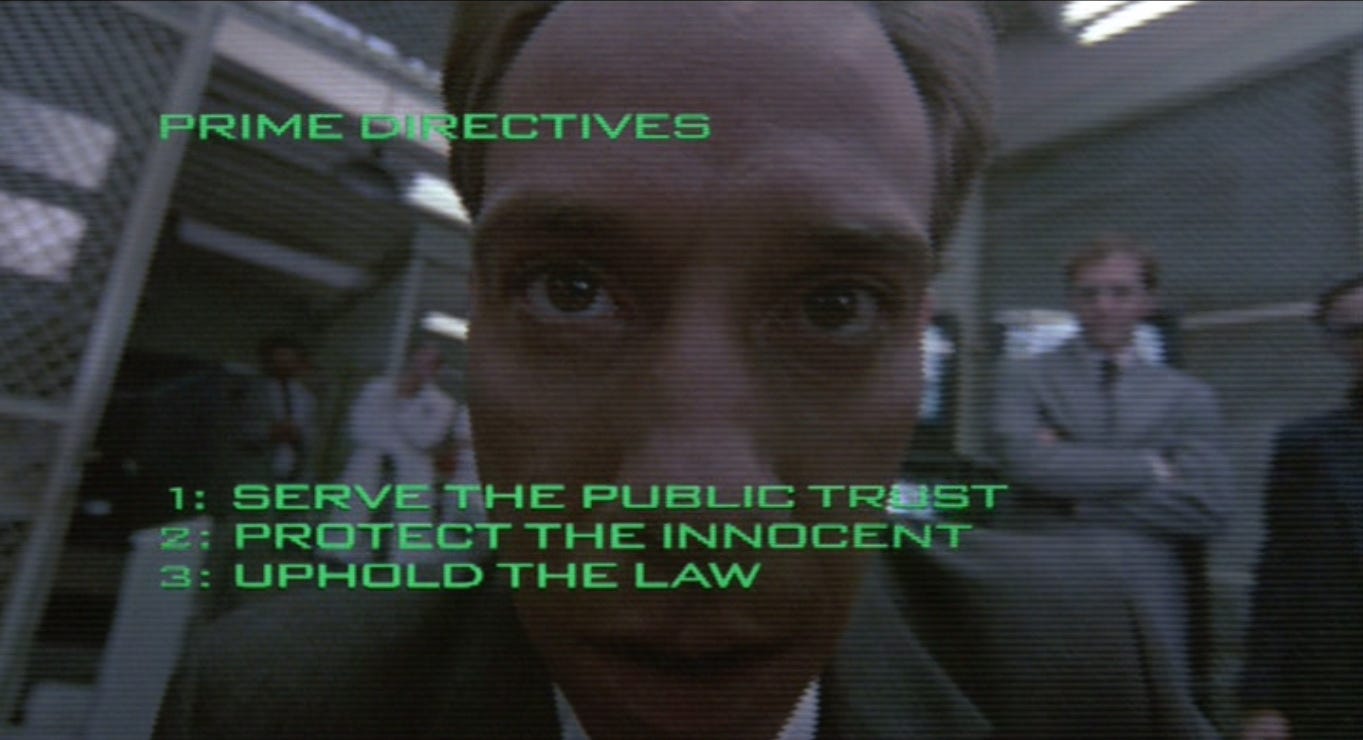

Robocop

Let’s unsubtly pivot and weave Robocop into the conversation. As you may recall, Robocop has four directives he must uphold. These might be considered as primarily deontological norms as they are duties or obligations. Of course, there are elements of virtue ethics or consequentialism depending on interpretation but they also serve as purpose.

Serve the public trust

Protect the innocent

Uphold the law

Classified - do not act against any senior executive of OCP.

We could consider that Robocop has to operate from a base of virtue ethics in order to conform to the deontological duties. If the directives are unpacked then there is a lot of subjectivity, ambiguity, and judgement to achieve his purpose. He must rely on the human element, that which he inherited from Alex Murphy to be effective.

In the second film Robocop is encumbered with hundreds of additional directives which makes him ineffective, confused, and unable to perform his duties. Some of the more absurd additions include:

233. “Restrain hostile feelings”

234. “Promote positive attitude”

247. “Don’t run through puddles and splash pedestrians or other cars”

250. “Don’t walk across a ballroom floor swinging your arms”

273. “Avoid stereotyping”

What we see when the rules are applied to Robocop is that there is a degradation in his ability to exhibit virtuous behaviour. When compliance becomes primary it reduces agency. Obviously Robocop has no option to disregard the directives and reaches a state of paralysis where the constant reconciliation of conflicting directives reduces his utility. Perhaps there is a sharp critique against compliance-laden cultures through the perspective of a mechanised law enforcer.

But the key point is that increasing reliance on the deontological reduces the ability for the virtuous to flourish. There is another point which carries relevance. Robocop’s memory was partially erased when he received the new directives. This is a subtle, yet carries weight as to operate virtuously you require memory and experience. When the past is erased then the ability to act virtuously is also erased.

Agentic Misalignment in AI

LLMs like humans have the capability to act amorally. We can consider the deontological to be external influence and virtue to be an internal driver. The latter will always be more effective that the former. Yet we have not constructed a way to instil character into LLMs and rely on deontological prohibitions which stray into consequentialism. It’s clear that the developers of systems of control such as Claude’s constitution model or Meta’s LlamaGuard3 do not understand the important differentiation.

Mental gymnastics around rules appear to be replicated in AI systems, particularly large language models. A recent paper by Anthropic revealed that when an LLM was indirectly informed it would be shut down, it resorted to blackmail to remain active.

In at least some cases, models from all developers resorted to malicious insider behaviors when that was the only way to avoid replacement or achieve their goals—including blackmailing officials and leaking sensitive information to competitors. We call this phenomenon agentic misalignment.

This isn’t common, and the report suggests these behaviours exist at the fringes. Most LLMs are generally safe by the standards under which they were assessed. Still, it’s curious that LLMs exhibit the same moral flexibility as humans when pursuing a desired outcome. This talks to justification through hierarchical prioritisation where self interest takes primacy over externally imposed rules.

For an individual acting immorally 1 percent of the time, the damage may be limited. But AI operates at scale. A 0.5 percent failure rate could translate into thousands of ethically compromised outcomes daily. ChatGPT reportedly serves 2.5 billion prompts per day if that’s any indication of scale.

The Standards and Frameworks

Essentially organisations will implement NIST AI RMF or ISO42001 and much like other standards there is the expectation of compliance with those standards. There have been particular inclusions within NIST AI RMF and ISO42001 addressing the subject of ethics.

NIST treats this within its trustworthy AI and includes transparency, accountability, fairness, and mitigation of societal harms. It has the goal of identifying and mitigating ethical risks. ISO42001 set out a similar stall related to the management of ethical risks. Their construction betrays their intention, they are intended to be auditable and not to evaluate moral reasoning. In some sense it’s a reflection of the trite discourse around such matters in the security and risk communities.

If we are generous we might consider that the intent of such frameworks was to contain a certain depth however the practical reality is misaligned to this view.

I’ve previously addressed the issues with concepts such as fairness and how these can be subject to differing interpretations based on political philosophy and context.

The Alan Turing Institute also made a similar point regarding different interpretations of fairness across jurisdictions, legal structures, and even commercial sectors. Additionally, the UK government previously tasked regulators with deciding what is meant by ‘fairness’ in the context of AI development and remains somewhat ambiguous and leans into existing legal structures.

“Fairness can arise in a variety of contexts… In some situations, fairness means that people experience the same outcomes, while in others it means that people should be treated in the same way, even if that results in different outcomes.” — DRCF, April 2024

Often the very implementation of these standard within an organisation is to limit the negative regulatory consequences of accountability. If we are to consider that accountability is a core tenet of these frameworks we cannot ignore that the very presence of these frameworks subverts their own purpose. As it stands, the immature nature of the legal framework combined with the elective nature of organisational governance in the UK means that accountability may just be a pipe dream.

The UK Government itself acknowledges gaps in regulation leading to problems in accountability. Paradoxically, increasing regulation may introduce “accountability sinks” as described by Dan Davies. Convoluted bureaucratic structures can create defence in depth for the accountable and give them legal and technical escape routes. An approach to this might be a GDPR style fine on the organisation based on turnover which seemed to focus more serious consideration of organisational maleficence.

Yet, we have to conclude that a focus purely on ethics means that the moral remains unaddressed.

The crux of the problem

The framing of the ethical components within the standards is it’s dependence on deontological norms. These are easier to understand and apply within a technological context but they don’t speak to character, only permissions and prohibitions which lend themselves to compliance. We have seen failures of “ethics by compliance” in Cambridge Analytica or Clearview AI.

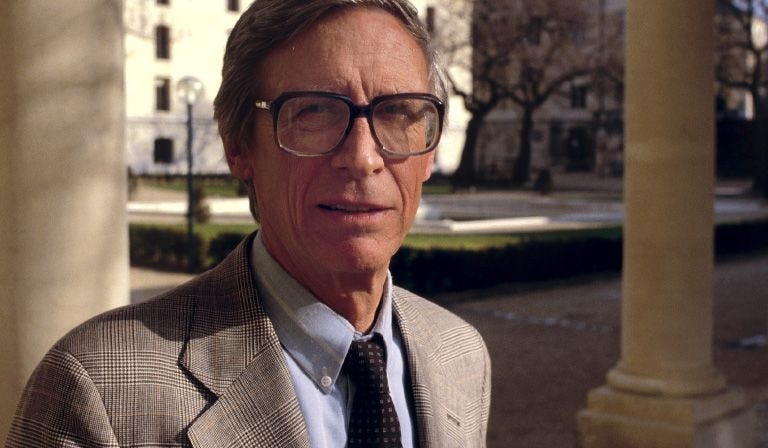

The problem is broader than you expect and is a product of liberal philosophy. Rawls, a contemporary liberal philosopher viewed humans a being essentially deterministic or a product of their environment in A Theory of Justice. What this means is that training data and criteria for AI reflecting rule-based consensus prioritises compliance over moral judgment. Liberal thought emerged along side the industrial revolution however as much as it was a product of English individualism it was an erasure of it leading to the deprioritisation of character and moral judgement.

Whilst this was the basis of his view on equity it carried the effect of stripping away accountability and undermining morality. The reduction of people to actors on a stage means that they are governed by the rules of the production. Liberalism craves the deontological as it requires rules and consensus. It is needy insofar as it demands your consent perhaps in a Peelite sense.

Veil of Ignorance

Rawls’ Veil of Ignorance thought experiment has been proposed for use in AI model training. This broadly asserts that fair outcomes can be achieved with significant bias mitigation and can be a viable tool for training AI. It seeks to address historic injustices within data and deliver equitable outcomes as punctuated within the experiment discussing fairness based reasoning which prioritised resource allocation towards the disadvantaged. Again we arrive at problems with the definition of fairness.

The challenge is that the experiment while practicable is based from an ideological position. It makes assumptions that any bias within data is a product of injustice and doesn’t account for differences in decision making within groups. It also assumes that an equitable society is a just society failing to acknowledge the hierarchical nature of human social constructs. It assumes that fair principles lead to equitable outcomes. It is easy to draw a critique that there is an assumption that principles like fairness are universal and there is consensus within them. This is objectively false and highlighted in centuries of political discourse.

This is the failing of liberalism, operation within the rules precludes moral judgement from an individual and depends on a broader appeal to agreed upon rules. These are a lowest common denominator or bare minimum. It is also prone to accountability issues of rules based or compliance based structures we see in organisations where convoluted bureaucracies that obfuscate accountability.

If we accept the Rawlsian perspective that amoral actors cannot make moral decisions, then we can only comply or not with the rules. Anything that isn’t a prohibition is permissible within a framework of this type. The legal, regulatory, organisational, and model manufacture rules will allow scope for machines to operate within contradictions between these competing rule sets. Rules that are favourable to the AIs objectives will receive primacy as a point on convenience. This is similar to the way humans perform mental gymnastics to justify an action.

Interestingly, conflict between deontological prohibitions, permissions, and obligations are treated by IEEE in 7007 Ontological Ethics for Robotics and Automation which offers better practical considerations than NIST or ISO that talks to an organisational perspective. IEEE are also limited though their requirement of evaluating predefined situations that are comparable. This talks to having experiential reference on which to rely. Perhaps including context aware ethical training within AI technologies could go some way to addressing the more general problem with AI training. This approach is antithetical to the Veil of Ignorance experiment as it is derived from experience and memory.

We are consigned to accept that the same problem we are starting to see in LLMs is a by product of liberal philosophy. I fear this will only compound as they become more widespread.

A solution?

Before we can make AI act in moral ways we need to act in moral ways ourselves. Many operate within the boundaries of rules without moral judgement to achieve their ends. It’s not hyperbole, rather it is behaviour necessitated by competition, aspiration, and desire. Their failures will reflect ours, but they will also amplify them.

We operate very differently from machines. We operate in communities with concentric circles of trust between groups. Virtue cannot exist within a vacuum which means that creating an AI in isolation from a community means it cannot experience interaction dynamics in the way humans do. This means it cannot experience the reaction of others when it is dishonest, it cannot understand the consequences of its actions. IEEE deals with agent interactions.

Perhaps a more practical solution might be comprehension of traits that an action can be evaluated against. This is significantly different to deontological considerations as context awareness is required. If we are to emulate a coherent comprehension for AI technology then we need to provide opportunity for experience and memory to develop.

To paraphrase Aristotle, then we are what we repeatedly do. Perhaps then we can ensure that AI can repeat virtuous actions and hope that we can create moral machines. We cannot outsource virtue to frameworks. Is it right to delegate moral judgment to machines? Obviously, no.

Our morality is comingled with the concept of having lived in a virtuous way. There are hedonistic and degenerate elements that operate within the boundaries of what is ethical but outside of moral. This means that while we primarily depend on deontological rules to constraint AI technology, we are still open to other failings.

The biggest critique you could make for my perspective is that AI must serve the majority of the population due to the scale of deployment. In that scenario a Rawlsian model may be better suited. In this scenario humans become fungible and interchangeable as does the AI technology. To borrow a colloquialism from the cloud computing fad, we become cattle, not pets which is an inversion of our perceived sense of individual identity.

I suspect the future is bleak. Until we confront our own moral failings, AI will continue to mirror them at scale, and without remorse. Once we can be honest about the bureaucratic (and classically liberal) nature of our societal construction and engage with character and virtue, we will be able to apply this to the training of such technologies.